People often ask us, “What’s the perfect boat for cruising the ICW?” Our answer is simple: “There is no such thing as a perfect boat.” Everybody has different tastes, skills, and bank account balances. Besides, the perfect boat for negotiating Jekyll Creek (ICW Mile Marker 683) may not be the best for crossing the notoriously choppy sounds of North Carolina (ICW Mile Markers 63-186.) Selecting a boat is all about tradeoffs. You just need to decide what features are most important to you.

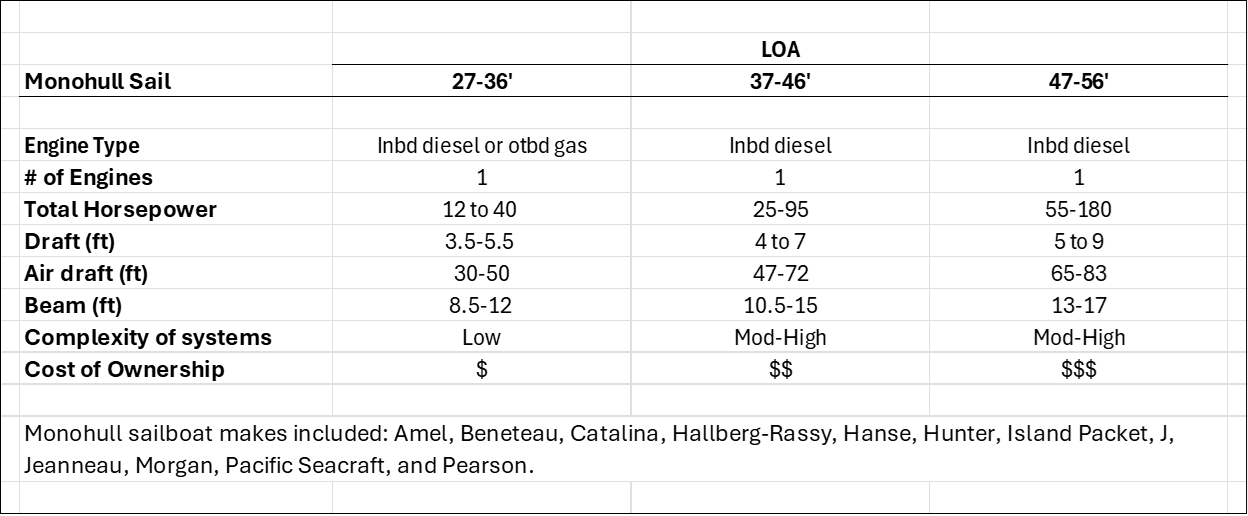

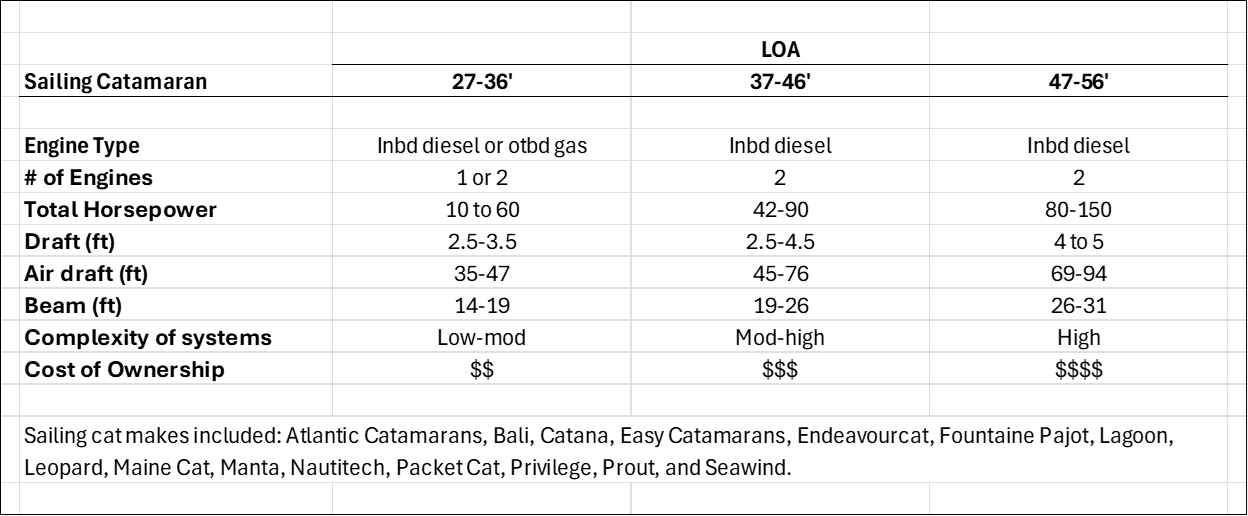

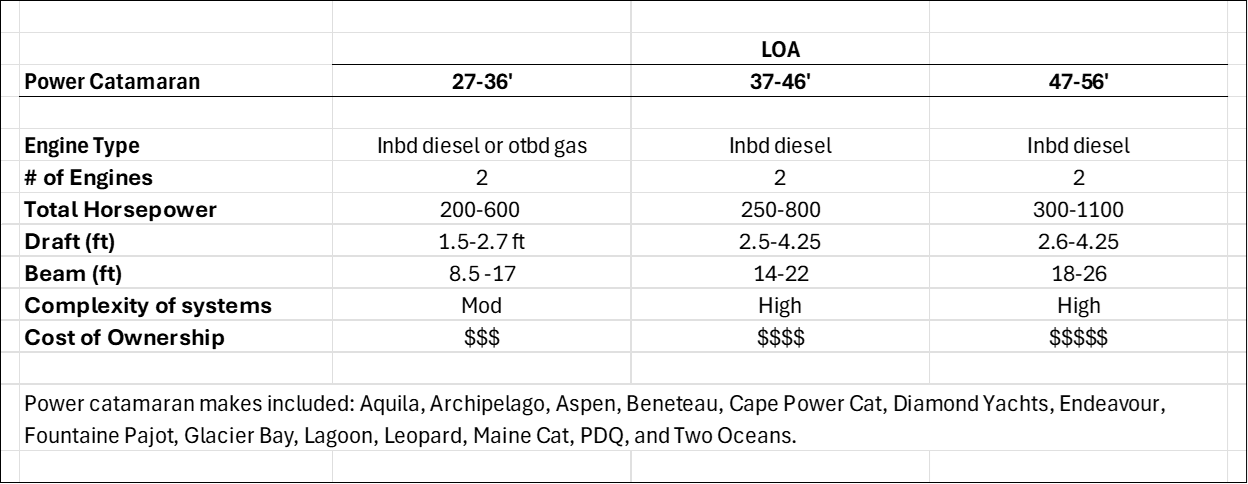

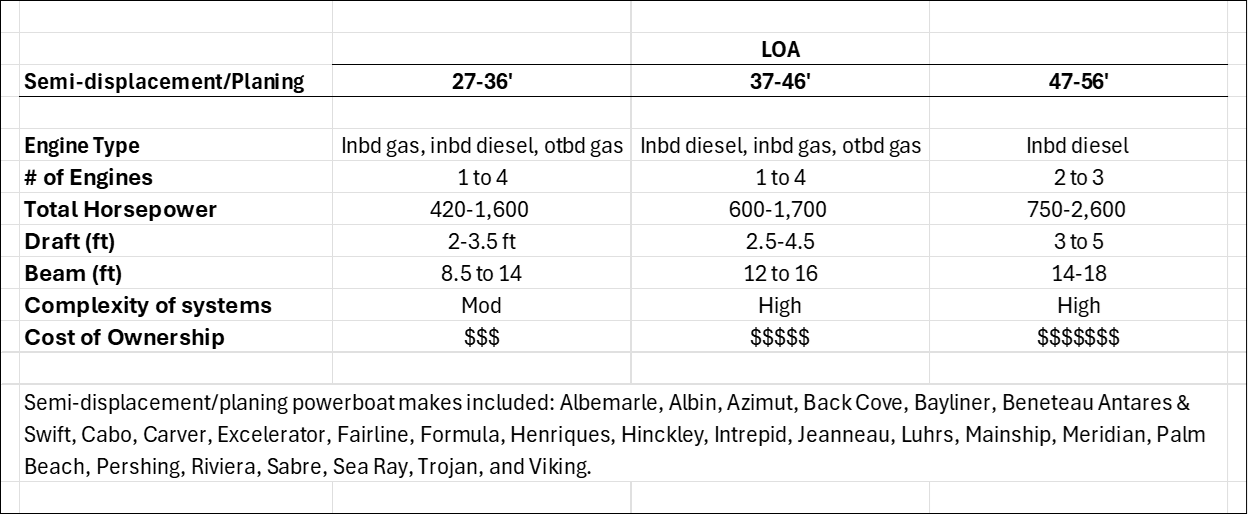

Most ICW cruising boats can be separated into five categories: 1. monohull sailboats, 2. sailing catamarans, 3. trawlers, 4. semi-displacement/planing power boats, and 5. power catamarans. We’re going to compare the characteristics of the boats in these categories and highlight some of their common features. We’ll focus on practical aspects of design that affect a boat’s maneuverability, ability to survive a grounding, maintenance requirements, and cost of ownership. Specifically, we’ll compare engines (number, type, and total horsepower), draft, beam, air draft, complexity of systems, and cost of ownership.

Engine types include inboard diesel, inboard gas (usually with a sterndrive), and outboard gas engines. Now, you may be thinking: “I’m a sailor, so this focus on engines isn’t all that important to me.” Trust us, on the ICW, even the most dedicated sailors motor most of the time.

Gas engines (both inboard and outboard) are quieter and less smelly but tend to have shorter lives and lower fuel efficiency than diesels. A gas engine, obvioulsly, requires you to carry gasoline, which is more volatile than diesel fuel.

Compared to inboards (gas or diesel), outboard engines weigh less, don’t take up space below deck, and can be tilted clear of the water. Being able to tilt out of the water reduces corrosion, fouling, and drag (helpful for sailboats). The sterndrives of gas inboard engines can also be trimmed up to reduce draft, but they cannot be lifted completely out of the water. Small outboards can also be removed from the boat for repairs.

There are pros and cons related to the number of engines. Having multiple engines makes it easier to maneuver and redundancy increases safety. But having multiple engines requires more maintenance, thereby increasing costs. The props of multi-engine boats tend to be more exposed and, therefore, more vulnerable to damage during a grounding. Total horsepower correlates with fuel consumption and cost of maintenance.

Draft is not as crucial on the ICW as most people believe. There are commercial vessels drawing 8-10 feet that regularly navigate the ICW. If your draft is 7 feet or less, you’ll be fine. A deep draft just means that you have to pass through the shallow areas of the ICW at high tide, limiting your choice of passage times.

Underbody design is as important as draft. Regardless of your draft, there is a good chance that you will run aground during a trip on the ICW. At that point, the design of your boat’s bottom will largely determine how much damage is sustained and whether you can free yourself. Whether you have a powerboat or sailboat, if you plan to travel much on the ICW, you don’t want your prop(s) or rudder(s) to be the deepest part of your hull. Your propeller is much safer if it is in an aperture or if there is a protective strut below it. The props and rudders on most twin-engine powerboats are vulnerable because they are offset laterally from the keel (if there even is a true keel) and rarely have any type of protective structure.

Beam is an important consideration for marina dockage and associated fees. Boats with a beam greater than about 18 feet are often charged higher rates for dockage. Boats wider than this may not fit in a standard slip and must either be tied up to a face dock or pay for two adjacent slip spaces. Also, relatively few boat yards can handle these wider boats. With a limited number of boat yards available, wider boats can expect to pay more for haulouts.

Air Draft is only an issue for sailboats. Most fixed bridges on the ICW are advertised as having 65 feet of vertical clearance at mean high water. Since this is a mean, or average value, you can expect times when the clearance is less than 65 feet (and other times when there is more). However, many fixed bridges on the ICW have slightly less than 65 feet of clearance during mean high water. If you have an air draft greater than 62 feet, you need to pay closer attention to water levels and bridge clearances.

Complex systems, such as diesel generator(s), satellite internet, bow thrusters, networked camera systems, multiple air conditioners, multiple refrigerator/freezers, a windlass with a remote control at the helm, and a ton of other gadgets, can make life easier and more comfortable. But every electrical or mechanical device on your boat is going to fail at some point. The more of these devices you have, the more often failures will occur. When breakdowns of complex equipment happen, repairs often require skilled technicians, costing time and money. For this category, we had to make broad generalizations, since two seemingly identical boats can differ in the amount of equipment they have. Just remember that convenience comes at a cost.

Cost of Ownership dictates many of our boat buying decisions. The best boat for you is the one you can afford to own. Don’t just think about the purchase price. The real expense of a boat is in the operation, maintenance, storage (dockage, mooring fees, and yard storage), and insurance. In our simple analysis below, the cost of ownership line is a subjective approximation of all the costs involved. Take it with a grain of salt.

Now, let’s look more closely at the features and tradeoffs of these five types of boats. First we’ll look at the two types of sailboat, followed by the three powerboat categories.

Sailboats: Monohulls & Catamarans

Of all the types of boats considered here, monohull sailboats are the cheapest to purchase, operate, and maintain, on average. However, they are the slowest and, arguably, the least comfortable to live on. Sailing catamarans are roomier, more stable, and more comfortable, but they are more expensive than monohulls.

Catamarans tend to have taller masts than monohull sailboats of the same length. Most monohull sailboats greater than 47 feet and catamarans greater than 42 feet in length are excluded from the ICW by their mast height (65 feet or higher). However, air draft also depends on the type of rig. For example, a 45-foot sloop is likely to have a taller rig than a 45-foot ketch. Many catamarans have fractional sloop rigs, which feature a very tall mast. However, some cat owners have their rigs shortened to fit under the ICW bridges.

Draft and underbody design vary greatly among monohull sailboats (full keel, fin keel, keel/centerboard, swing keel, and lifting keel). Some performance-oriented monohulls, especially those over 47 feet, have drafts deeper than 7 feet. In a grounding, a monohull with a full keel and attached rudder, or a fin keel with a skeg-mounted rudder, would be less likely to suffer damage than one with a fin keel and spade rudder. Unsupported spade rudders are vulnerable to impact damage during a grounding. Twin rudders and keels with wings or large bulbs are particularly vulnerable to damage during a grounding I and will hinder your ability to extricate yourself once you are aground. These protrusions prevent the boat from healing over and dig into the bottom, acting like anchor. Ironically, the shoal draft versions of monohull sailboats can be more vulnerable than their deeper draft counterparts because the shoal draft boats receive less protection from their stubbier keels. In many shoal draft monohulls, the rudder is as deep as the keel. With a standard keel (deep draft version) extending below the bottom of the rudder, the keel usually hits bottom first and stops the boat before the rudder makes contact.

Catamarans tend to have shallow drafts and some have underbodies that are vulnerable. Many have small fin keels that are deeper than their rudders and saildrives (or props/shafts) and a few have outboard motors and retractable rudders that allow them to sit on the bottom quite happily. But for many cats, their fixed rudders and props/saildrives are their lowest points. Once aground, catamarans can’t be heeled over to reduce their draft, making them more difficult to free from the bottom than most monohulls.

Sailing cats move relatively easily through the water and often motor at faster speeds than sailing monohulls. Almost all sailing monohulls have a single engine; smaller ones can have an outboard or a diesel inboard (or even gas inboard for older boats) and larger ones have a diesel. Sailing cats over 35 feet have twin diesels; smaller ones can have one or two diesel inboards or outboards.

To maintain stability under sail, sailing catamarans tend to be very wide. Most sailing cats that are over 37' LOA have beams greater than 18 feet. This is not necessarily a deal breaker for the ICW, but it can make life more complicated and expensive.

Powerboats: Trawlers, Semi-displacement/Planing, and Power Catamarans

The distinction between trawlers and semi-displacement/planing (“planing”) powerboats can be blurry. Just about any powerboat seems to be called a trawler these days. We tried to limit the trawler category to just powerboats with full displacement hulls. Most small power catamarans are designed for sport fishing. We limited our investigation to catamarans with enclosed cabins and that appeared to be intended for cruising.

Among powerboats, trawlers tend to have the lowest cost of ownership and semi-planing powerboats have the highest. Horsepower and fuel consumption of trawlers are lower than those of planning boats, but trawlers are considerably slower. Power catamarans are intermediate between these extremes with regard to horsepower, fuel consumption, speed, and cost of ownership.

For all three categories of powerboat, there is a variety of propulsion configurations. Across the board, the larger boats tend to have diesel engines (often twin engines). The smaller ones have a variety of propulsion systems. Small trawlers can have a single diesel engine or outboards (single or twin). Small planing boats can have 1 or 2 diesels, 1 or 2 gas inboard engines (usually with a sterndrive), or 1 to 4 outboards.

Trawlers tend to fare well in a grounding. They usually have substantial keels that extend deeper than their prop(s) and rudder(s). Single-engine trawlers, because their prop is very well protected, can heel over, making it easier to extricate them from a grounding. Most power cats are a bit vulnerable during a grounding, as their props and rudders are the deepest part of the hull, and they can’t be heeled. Planing boats, which are designed for speed, usually lack a true keel or just have a very small keel. In many planing boats, their props, shafts, and rudders hang down far below their hull. Therefore, they really dislike being run aground. Some newer planing boats have forward-facing props, which are more efficient, but much more likely to be seriously damaged by a submerged object or the seafloor. Forward-facing props may be great on the open ocean but are a bad idea for an ICW cruiser.

Power catamarans are a bit narrower than their sailing counterparts and the beams of some of the smallest power cats are surprisingly narrow because they are designed to fit on a road-legal trailer. However, compared to the other powerboat classes, power cats are stable and comfortable, and tend to be beamier, roomier, and more stable. The engine compartments of power cats tend to be cramped.

As you can see, each of these designs has its strengths and weaknesses. Rest assured, you will find all of these types of boats navigating the ICW. Choosing the right boat is all about finding the perfect mix of tradeoffs for you. Which do you choose?