For cruisers on the East Coast of North America, making a run down the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) is a rite of passage. For some, the ICW is both the route and the destination. For others, “The Ditch” is just a way to bypass Cape Hatteras, which has a fearsome reputation among mariners.

The ICW is infamous for its narrow, shifting channels, shallow water, swift currents, low bridges, and heavy vessel traffic. But for many cruisers, the rewards–tranquil waters, expansive marshes, ancient forests, undisturbed barrier islands, abundant wildlife, and some of the most picturesque and welcoming towns on the East Coast–make the ICW journey worthwhile. Love it or hate it, having certain knowledge and skills can make a transit of the ICW less stressful and far more enjoyable.

Learning how to avoid grounding is of paramount importance. When you can’t avoid it, it helps to know how to do it “properly.”

These tips from Damon & Janet Gannon’s how-to guide, called Thriving on the ICW can help you successfully negotiate this waterway.

1. Make sure you are actually staying within the channel. At most of the notoriously shallow spots on the ICW, the main problem is not the shallow depth, per se. The real issue is the narrow width of the channel combined with the effects of a cross-current or cross-wind. (Chapter 4)

2. Plan your arrival times at the shallow trouble spots to coincide with a rising tide. Try to get there 2 to 4 hours after low tide. IFyou run aground, you’ll then have 2 to 4 hours of a rising tide to help get you free. You can find out where these trouble spots are from Aqua Map, Waterway Guide Explorer, and cruising guides such as the ICW Cruising Guide by Bob423. (Chapters 4 & 8)

3. Slow down! When the water gets skinny, limit your speed to just the headway needed to maintain steerage. Bump your engine(s) in and out of gear. If you have twin engines, keep one engine in neutral when feeling your way through shallow water (you can alternate engines). The seafloor throughout most of the ICW is soft mud. If you run aground at slow speed, you’re unlikely to cause damage and you’ll probably be able to free yourself. If your prop contacts the bottom, it’s much less likely to suffer damage if it isn’t in gear and spinning. (Chapter 4)

4. Beware of the nuns and cans! Along the ICW, except near the major ports, most of the channel markers are daymarks (wooden pilings with red triangles or green squares on top). However, you will also occasionally see small red “nun” and green “can” buoys. Floating navigation buoys on the ICW often indicate areas that are shallow and shifting. Where the channel is actively shoaling, the aids to navigation have to be moved frequently, so the Coast Guard uses small buoys that are easy to reposition. That’s your signal to be extra careful, as the channel may have shifted since the buoy was last repositioned. (Chapter 4)

5. Don't cut corners. Because of the way that currents move sediments, the water is usually shallowest along the inside and deepest on the outside of the curves. Stay wide while going around curves, but remember to keep clear of oncoming traffic. (Inland Navigation Rule 9) (Chapter 4)

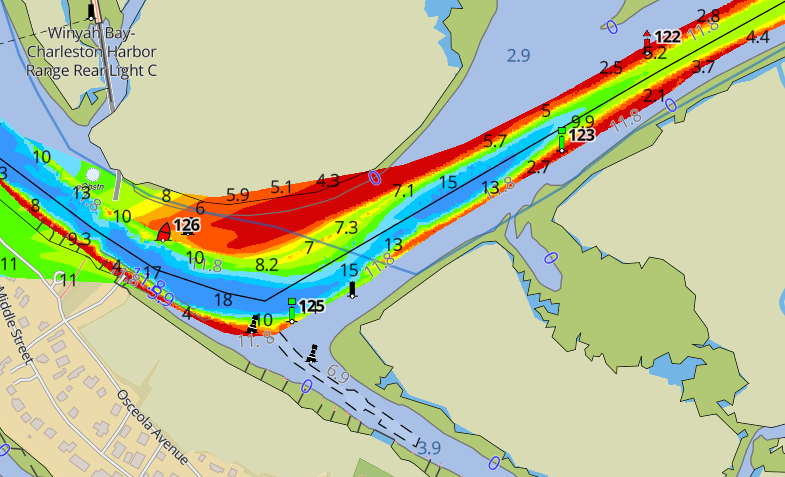

6. Expect the water on the ICW to be shallower-than-normal when the wind has a westerly component and deeper than normal when it has an easterly component. Onshore winds–such as during a nor'easter storm–increase depths in the ICW by blowing ocean water into the estuaries via the inlets. Offshore winds–such as the westerlies following a cold front–do the opposite. The closer you are to an inlet, the greater the effect will be. It’s not uncommon for the wind to change the water depths and bridge clearances by 1 to 2 feet, depending on the wind’s speed, direction, and duration. (Chapter 2)

7. Stay current on the current. Tidal currents on the ICW are strongest at the inlets and weakest about halfway between two inlets, on the back sides of the barrier islands. The current during the outgoing tide is often stronger than that of the incoming tide because of the additional outflow of river water. Currents affect your boat’s movement through the water and your ability to steer. Just because your bow is pointed in a particular direction doesn’t mean that’s the actual direction in which you are traveling. When negotiating a narrow channel, don’t just look at the channel markers ahead of you. Even if your bow is pointed at the next set of channel markers, a cross-current could be setting you sideways. When you pass an ocean inlet or an intersecting marsh creek, expect sudden changes in the direction and speed of the current, which will probably push you sideways. To tell if you are being pushed out of the channel by the current or wind, look behind you for the markers that you just passed and line them up with the ones in front of you. (Chapters 2, 3, 4, 5 & 7)

8. Inlets are the gateways between the ocean and ICW. The single most dangerous thing that you will probably ever do in your boat is enter an inlet from the ocean. The consequences of running aground in the outer reaches of an inlet are far more dire than doing so inside an estuary. Most inlets shouldn't be used, especially by visiting cruisers. Along the Atlantic ICW (between Chesapeake Bay and Miami), try to stick with the 14 inlets that serve as deepwater shipping ports. The most favorable situation for transiting an inlet would be:

-

- Heading outbound, toward the ocean (at least for your first trip through that particular inlet),

- Daylight,

- Clear weather,

- Calm sea conditions, with no on-shore wind (no easterly component to the wind for entering East Coast inlets), and

- An incoming or slack tide.

If you are offshore and the conditions become rough, you will probably be better off by staying out in the ocean rather than attempting to reach sheltered waters by transiting through an inlet in dangerous conditions. (Chapter 6)

9. Use all of the navigation tools at your disposal. Redundancy is key. Don’t rely on just a single piece of equipment for navigation because electronic gadgets tend to have a short life expectancy aboard a boat. Start with the “Holy Trinity” of ICW navigation: Aqua Map, US Army Corps of Engineers depth surveys, and Bob423 ICW tracks. Whichever electronic charting system you use, make sure that the display is zoomed in. If you are zoomed out too far, the icon representing your boat can appear to be in the middle of the channel when your boat is actually outside of the channel. Although your autopilot is a helpful tool, don’t rely on it where traffic is heavy or obstacles are numerous (Inland Navigation Rule 5). Keep your VHF radio set to scan channels 13 and 16 to help you communicate with fellow boaters. (Chapters 4 & 8)

10. Always use the 3 C’s: common sense, caution, and courtesy. If, in the heat of the moment, you can’t remember which navigation rules apply or what you should do, just slow down, keep to the right, don’t impede other vessels, watch your wake, and be aware of your surroundings. (Chapter 14)

Remember that thousands of boaters successfully navigate the ICW every day. If they can do it, so can you. Rest assured, you probably will run aground and it (probably) won’t be the end of your world. It’s just part of the ICW experience.

Article by:

Damon & Janet Gannon

Bio:

We are a couple of sailing marine scientists/teachers/writers. We've been "sciencing" and sailing together for over 25 years. In 2023 they took a year off to go cruising aboard their current boat, a Pacific Seacraft 37 named Fulmar. Their canine crewmate is a fair-weather sailor who prefers inland waters. Check out their other blog on cruising and science, called Adventure Blue.